A brief biography of

Thomas Hart benton

History & Biography of Thomas Hart Benton

An Open Door: Relating to Benton through his lithographs

Thomas Hart Benton (1889-1975) was a cantankerous connoisseur, an outspoken man with big ideas, and one of the most famous and controversial artists in America in the first half of the 20th century. As a plain-spoken Regionalist whose techniques and interests often looked to the past, he stood at odds in many ways with an art world focused on Modernism’s new ideas and values. But a departure from Modernism’s rejection of the past didn’t mean he wasn’t in touch with the present world around him: he made art that the everyman could relate to and afford, and in so doing became an icon and champion of the Midwest.

Benton’s lithographic work stands firmly in the canon of America’s most treasured prints. His work offers a willing hand to its viewers, extending gracious access through style, subject, and proliferation of prints, and even today, a persistent Benton market shows the strength of the bond between artist and viewer.

Navigating the American Style

After 1913’s famed Armory Show brought Modernism to the new world, New York quickly followed in the footsteps laid forth by Paris, as innovative American artists came up with numerous new takes on increasingly non-objective abstraction and conceptual art. In fact, by that time, Benton had left his native Missouri to study in Paris and had already returned to New York in 1912. He briefly tried his hand in abstraction of various types in those early years, but despite his presence and connections in the two cities at art’s forefront, he quickly changed course back to representational work. Though he greatly admired the work of Cezanne and other modern masters, Benton consciously resisted what he believed to be a trend of American artists copying the great French painters.

Perhaps the push and pull of his developing style stems from the dichotomy of the environment in which he grew. Benton was not only the son of a sensitive and artistic mother who encouraged his development, but also a rigid father who discouraged Tom’s artistic pursuits. In many ways, these two personalities are reflective of European and American artistic audiences of the time as well: while Europe was fascinated by the sophisticated, the United States placed greater value on austere realism. So Benton studied abstraction and used its ideas as underpinning for his work — even later helped shape it, in no small part because of his role as Jackson Pollock’s mentor — but all of his best-known and loved creations stay quite representational.

To this day, his decision to abandon Modernism is the source of great derision among many (though certainly not all) art critics and historians. However, it is also the one that gave him a platform with which to reach the American public, and specifically the Midwest and South. These populations — the blue-collar workers, farmers, small-town shopkeepers, country ministers, middle-class families– found it difficult to relate to the fast-advancing cutting edge styles of the art world. Modernists weren’t champing at the bit to show their work in these towns anyway. These vast swathes of Americans and the Modernist “elite” were on two sides of a locked door; neither side had much interest in seeing the other side of the wall. But Benton had spent time with those elites, learned a thing or two about painting, and opened the door.

Communion through Shared Experience

Not only was Thomas Hart Benton’s style reflective of what Americans valued and related to, but his subjects were too: he depicted scenes of American history and culture. His subjects often looked to the past, memorializing historical American individuals like Jesse James, or scenes full of significant political players in various state murals. He would also commemorate America as a place, with its disappearing rugged wilderness giving way first to rural farms, then steam-powered locomotives, and ultimately urban centers populated by steelworkers and movie stars. Benton would connect with American viewers by referring to their shared touchstones: the sounds of folk and country music, the stories of Twain and Steinbeck, the love of fishing or boating or exploring.

The simple act of Benton selecting a subject served to exalt the ordinary: the everyday acts of threshing wheat, producing tobacco, laying railroad tracks, or digging New Deal trenches became magical–even spiritual. For rural Americans to see their lives deemed worthy of artistic reverence by a painter of Benton’s stature and skill was novel: he saw them, they saw him, and there grew a shared respect. He’d create works of social realism, depicting the hardships of the working man’s life, advocating for those who had no voice. Even in Benton’s most high-concept work, where he’d illustrate mythological scenes, he did so through a relatable, contemporary lens, illustrating classical narratives with a cast of working class Americans. It’s no wonder that Benton found frequent commissions for public works: he created murals of the people, by the people, and for the people.

Lithographs: Affording the Opportunity to Own

Despite the growing love shared between Thomas Hart Benton and the general public, there stood an elephant in the room: the more Benton grew as a champion of the people, the less the working class audience could afford his paintings. With each composition intricately mapped out and diligently practiced, these were not objects he could produce for the masses. And if the cost barrier for the general populace was high then, it is higher now by magnitudes, with paintings regularly selling for six and seven figures. Fortunately for working class patrons both then and now, in the 1930s, Benton began producing lithographs, which stand as a more cost-effective means of owning one of his masterfully constructed scenes.

Benton first began to experiment with different methods of printmaking in the early 1920s, at that time a bit desperate for any means of income available. He first tried etchings and block prints, but those never amounted to much in the grand scheme of his oeuvre. In the scope of his printed works, he’s best known for his lithographs. Lithographs best suited Benton’s painterly style: drawn with a greasy crayon, lithography offers artists an opportunity to capture a full range of tones.

Benton created his first lithograph in 1929, a geometrically rendered view of an Oklahoma train depot titled The Station, produced in concert with legendary NYC printmaker George Miller. He’d go on to make a handful of other lithographs over the next five years, but it wasn’t until 1934 that Benton started to create lithographs in earnest, under the influence of a new means of distribution: the Associated American Artists (AAA). Formed by a man named Reeves Lewenthal, the AAA was created to help offer prints by some of the biggest names in American art at lower prices than ever before. It also helped to provide a steadier income for those artists, who were guaranteed a flat fee for each new lithograph they created. The AAA would distribute the majority of Benton’s lithographs over his final four decades of work, as documented by Creekmore Fath in his comprehensive catalog.

Benton utilized lithography as studies for his paintings, as well as reworking already completed paintings in lithographic form. As such, his prints are evidence of the artist working at his fullest. Not only are his lithos more than mere sketched out thoughts, they are quite often the same iconic images as some of his finest works. One marked difference though? Most of these lithographs were originally sold at a price of $5-10 apiece. Along with his famous murals, the lithographs are in some sense the most perfect embodiment of Benton’s defining ideal: art for the people.

Benton’s Lithograph Market Today

As you might imagine, Benton lithographs no longer sell for a few dollars. As with Benton’s paintings and ephemera, the prints too have steadily increased in value over the years. On the low end, pencil-signed Benton lithographs will sell for $1000-2,500 (given its condition isn’t a problem): generally a modest but tidy gain for owners who have held and enjoyed the work for years, and while it’s not pocket change, the barrier for entry isn’t too prohibitively high for collectors on a budget. More typically, a good quality Benton litho sought after by collectors generally sells in the $2500 to $6,000 range, while the best of the best can sell well into five figures.

So what makes a lithograph one of “the best”? What factors might drive the price? Good condition is always a prerequisite, of course: is the paper smudged, has the print been housed with acidic materials that chemically “burn” the sheet, or has the sheet darkened due to excessive light exposure over the years? More to the point though, individual collectors will look for different things: pre ferred localities, scarce editions, specific subjects, and personally favored images. The more boxes that a print checks, the more bidders will stay involved as the price creeps up at auction.

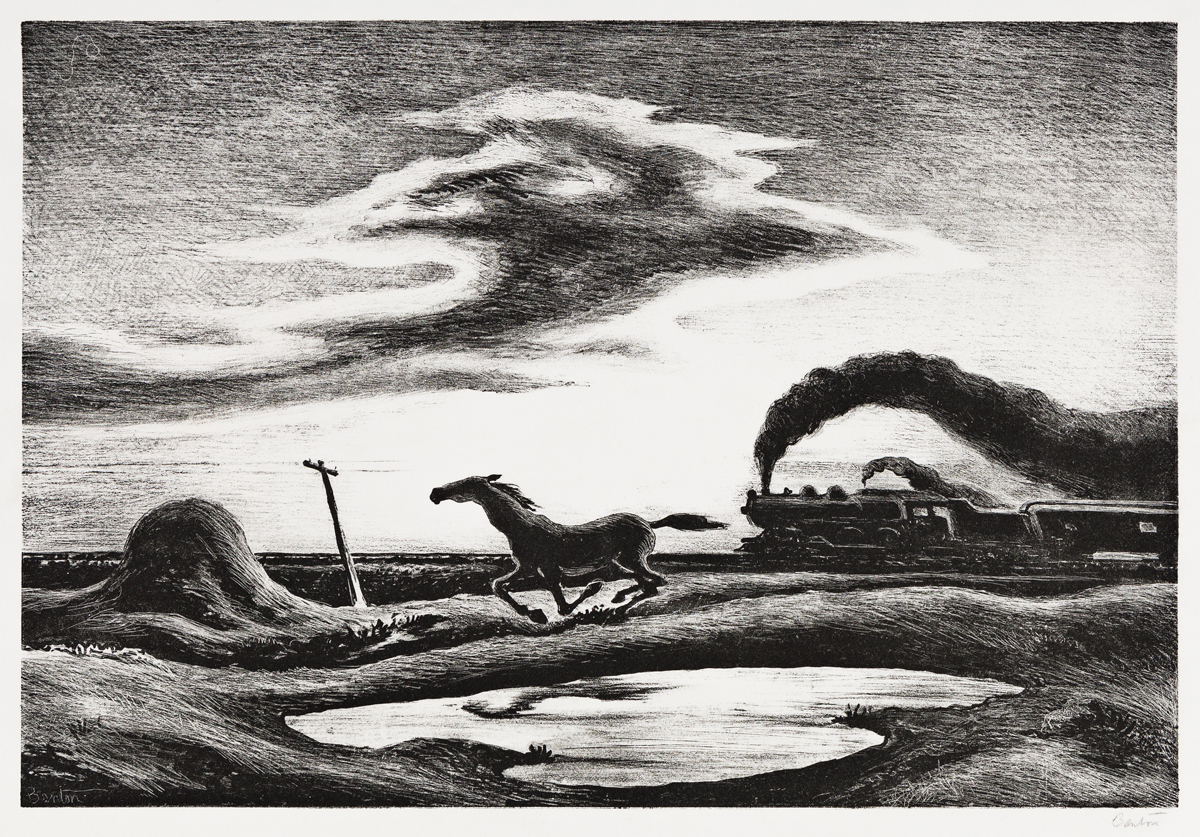

For example, Going West (1934) is one of the masterpieces of Benton’s lithographic output, a depiction of a steam locomotive flanked by telegraph poles, speeding through open territory as smoke billows expressively behind. When this print arrives at auction, copies in the signed edition typically sell for over $25,000. There are a few factors that contribute to that hefty price point: first, its edition size is just 75, because it was produced before AAA distributed Benton’s prints in editions of 250-300. It was also produced at the height of Benton’s fame and influence in the mid-30s, and his skill shows in the dynamically and expressively rendered subjects. Notably, Going West also features a steam locomotive, one of the most popular Benton motifs, which features prominently in other lithographs that demand a premium, including Jesse James (1936), The Race (1942), Wreck of the Ol’ 97 (1944), and Running Horses (1955). Another favorite motif, perhaps for their substantial narrative intrigue, are Benton’s portrayals of old folk songs, such as Coming Round the Mountain (1931), Frankie and Johnnie (1936), I Got a Gal on Sourwood Mountain (1938), and Ten Pound Hammer (1967).

Whatever factors attract an individual to bid on a specific lithograph at auction, this much is clear: the impact of Thomas Hart Benton is lasting. The same mix of magic and familiarity that reached an unlikely, broad audience in the 1930s still finds a voracious and appreciative public today.

Literature:

Adams, Dr. Henry. Thomas Hart Benton: Discoveries and Interpretations, University of Missouri Press, Columbia, 2015.

Benton, Thomas Hart. An Artist in America, University of Kansas City Press, Kansas City, 1951.

Fath, Creekmore. The Lithographs of Thomas Hart Benton, University of Texas Press, Austin, 1990.